It’s fair to say that many wine lovers would be hard pushed to pinpoint Moldova on a map, let alone realise that it is a country with a very long winemaking history. Sandwiched between Romania and Ukraine, most of Moldova has a continental climate, influenced by the Black Sea just to the south (though Moldova has no coastline, another part of this small country’s history at the hands of bigger neighbours).

What Moldova has, a shock to most people, is 112,000 hectares of planted vineyards, 81,000 hectares being “noble” varieties, where fifty different grape varieties are grown, a mix of indigenous and international. That actually equates to more vines per person than anywhere else in the world.

There are only three designated Moldovan wine regions, however, and those were only recently mapped and delineated as protected geographic origins. These are (see map below) Codru, the largest, in the north, Valul Lui Traian in the south, and Ștefan-Vodă (central southeast).

Why all these vineyards? After all, the Republic of Moldova is Europe’s smallest country. The history of Moldova as a wine producer, the reason why we never heard of her wines even as Bulgarian wines, and then Romanian bottles, hit our shores after the fall of Communism, is one that is linked to Russia. Back in the early 2000s 60% of the wine drunk in Russia was from Moldova, which in the Soviet era was a major supply source for the “mother” country.

In 2006/7 there was a clampdown, following which the amount of wine exported to Russia fell dramatically. Then, in September 2013 Russia banned the import of all wine from this small and very poor country. Ostensibly it was because of traces of plastic in wine, but it has been pointed out that these levels were lower than those found, and tolerated, in Russian drinking water. Of course, it was for more political reasons, similar reasons to those that leave Moldova without any Black Sea ports. Muscle flexing is always the way, it seems, in this region. Nevertheless, this ban had a devastating effect on a country reliant on agriculture, and where wine formed a major part of the agrarian economy.

Moldova has had to adapt, and quickly. It’s quite amazing that it has done so. A London Tasting on 10 October showed just how far Moldova has come, but of course it also showed what needs to be done to really break through in European markets, emulating the success of other countries formerly in the Communist Bloc. I’m thinking particularly of Georgia.

The Tasting was organised by Novus BH Magister, set up in 2016 to bring the wines of Moldova to the UK. They were assisted by Caroline Gilby MW, well known regional expert, whose book The Wines of Bulgaria, Romania and Moldova was published this year. Caroline conducted two masterclasses during the course of the day. Novus, based in Guildford, brought seven producers and their wines to show to trade and press. I’ll let you know how I think Moldova needs to take the next step later, but if these are the best producers in the country, then the potential for sales into Western Europe should be high, especially as the prices seem extremely reasonable.

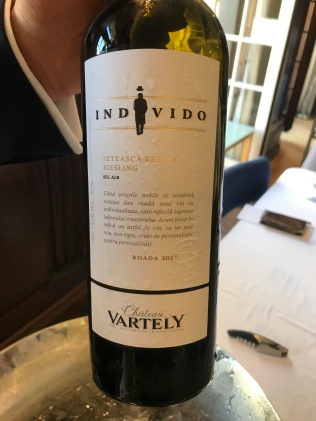

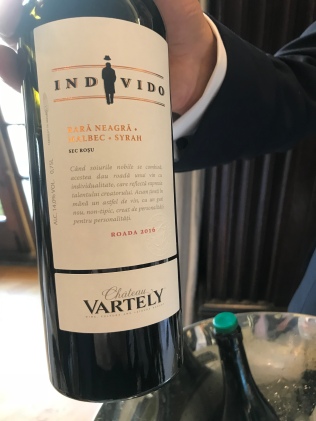

CHÂTEAU VARTELY

This is a large producer with 300 ha in Codru and Valul, although as a sign of what size can mean in Moldova, they are internally described as “small”. They are privately owned and began production in 2004. If they have a philosophy, it is to hold back on the oak (commendable), in order to produce fresh-styled wines, where possible from autochthonous varieties.

Fetească Regală-Riesling 2017 is clean and well made, more stone fruit than pure Riesling character. It has a dry texture. Rara Negră-Malbec-Syrah 2016 is nice and bright, brambly on the nose with deeper plum-plus-pepper on the palate. Smooth but bitter, 14% abv.

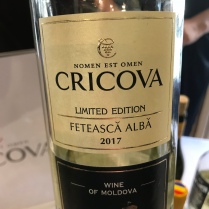

CRICOVA

Double the size of the previous producer, with 600 ha in the same two regions, this is one of the country’s largest wine estates. They have a production facility described as an “underground city” about 100 metres below the surface, with streets named after grape varieties and wines.

The conditions are said to be perfect for the ageing of sparkling wines. I tried “Moldova” 2012, an aged bottle fermented blend of 60% Chardonnay and 40% Pinot Noir. Most of this age must be post-disgorgement because it only claims nine months on lees. I’d have liked to have seen more ageing sur lies, because it was a little fat and lacked the precision of a good French Crémant, but perfectly well made and drinkable. The alcohol was quite high (13%) for a wine from the traditional bottle-fermentation method.

Fetească Albă Limited Edition 2017 had a lovely floral nose, reminiscent of spring blossom. The palate begins softly but then you get a lick of grapefruit acidity. Simple and clean but nice. Viorica 2017 is quite different, with a deeper nose, broader and with less acidity. There’s a touch of Muscat about it, but also stone fruit with a little mineral texture. It finishes with a hint of bitter quince. Viorica is, as those who follow Eastern Europe’s politics, a female first name. Viorica Dăncilă became Romania’s first ever female Prime Minister in January this year.

Fetească Neagră 2016 comes from a 8ha vineyard on the black soils, for which Moldova is famous. It has a deep colour, good legs, and a big dark fruited bouquet…and 14% alcohol. It scores first for its unusual, bitter but ripe, black fruits. It finishes quite tannic, but could be broached now, or aged. It also scores on price – £8.90 to the trade. None of the Cricova wines top £9.

EQUINOX

This is the estate of Constantin “Costia” Stratan, one of the country’s pioneers of modern viticulture. His Elemente 5 2015 is pretty expensive by Moldovan standards, £15.50 to the trade. It’s an extremely tiny production too, just 3,400 bottles of a blend of Carménère (49%), Merlot (17%), Shiraz (sic) (15%), Rară Neagră (12%) and Malbec (7%).

There’s the rich vanilla smell of new oak which immediately sets this out as a “modern” wine. In fact, there is only 25% new oak, but it comes through very sweet. The fruit is nice and smooth, but the tannins suggest that it is well equipped to age. It’s not really my kind of wine, but it’s very well made and could go head-to-head with many Bordeaux-style blends from Chile, or anywhere else for that matter.

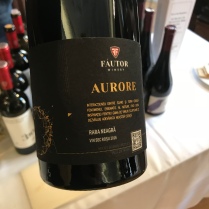

FAUTOR

There were some very good wines here from this Valul lui Traian producer, with 350 ha at their disposal from the Tigheci Hills. The two Altitudine wines are fresh and simple – the white (2017) blends Chardonnay with 20% Fetească Regală, and the red (2016), Cabernet Sauvignon with Fetească Neagră.

Aurore white (2017) is a characterful blend of Albariño and 45% Sauvignon Blanc. The red Aurore (2016) is comprised 100% Rara Neagră. One of my favourite wines overall, and under £10 to the trade, it sees six months ageing in assorted new oak, but that doesn’t dominate at all. I loved the bouquet, reminding me somewhat of Nebbiolo. A touch of tannin stiffens a very good long, savoury, finish.

The top white was, surprisingly, not a local variety here, but Sauvignon Blanc, fermented and aged (with bâtonnage) in new oak again – this Fumé Blanc 2016 has the distinction of being a rare wine made in this style that I like.

The most expensive red (£14.55) is called simply Negre. This 2016 is made from native varieties Fetească Neagră (70%) and Rara Neagră from a small six hectare plot on clay/sand. It is made using micro-oxygenation techniques, fermented in steel and then given the same six months in new oak as the previous two wines. It shouts out bramble fruit on the nose, but more oak seems to come through than on the previous red. Rich, tannic and spicy, impressive, but I preferred the style of the Aurore red, personally.

POIANA

This estate owns just 20 ha in Codru, all farmed organically. The wines are very well made, although the local varieties are clean and do seem almost international in style. This will appeal to the vast majority of drinkers, although the opinion forming minority might look for something a little different.

That said, of the two whites my preference was for the single variety Fetească Alba 2017 (pale, floral with green apple freshness) over the version blended with, and dominated by, 70% Sauvignon Blanc.

A 2017 Rosé was pure Cabernet Sauvignon, from 10-y-o vines on fertile black soil, well made although like many pink wines, it didn’t aspire to more than pleasant dry freshness. Fetească Regală 2017 had an altogether deeper bouquet, quite a broad wine (13% abv) with a stony, mineral, texture.

All these wines are fairly low production, 6,500 to 6,800 bottles, and all are made in stainless steel. I think these would have appeal despite them seeming quite “clean” (or perhaps because of that).

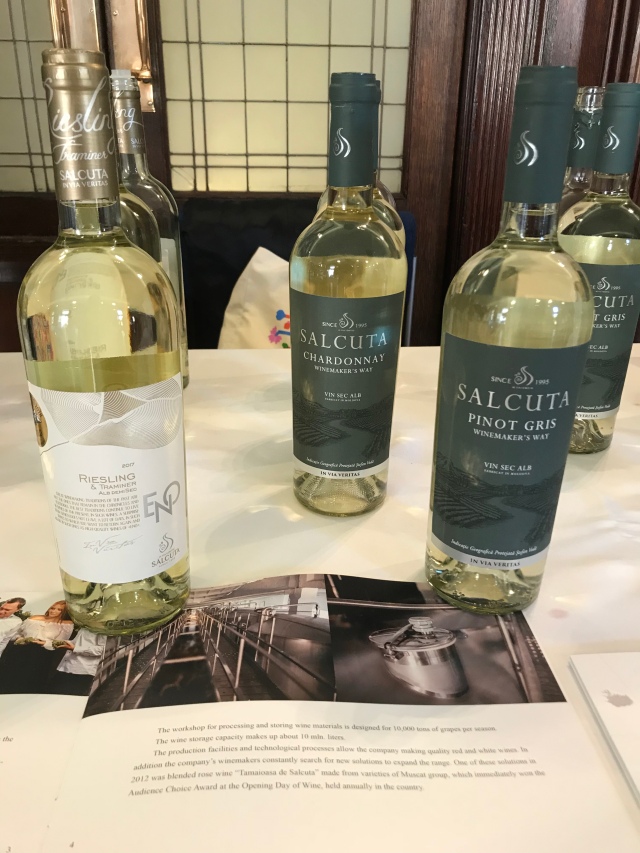

SALCUTA

Sometimes it’s hard not to be affected by the way in which a producer or their representative attempts to engage. Of course, the language barrier got in the way in some cases at this tasting, but Dina Pîslaru spent more time than anyone else explaining the wines of Salcuta, and Moldova in general, to me (thank you, Dina).

Salcuta owns 400 ha of vines in the Stefan Voda Region, the sunniest and driest wine region in Moldova, divided between three sub-zones: Salcuta (after which the estate is named), Tenetari and Ucrainca. Founded in 1995, they are intent, despite their size, on making wine just from their own vines. To this end they have established their own nursery for plant propagation.

With such a large production Salcuta makes many different cuvées (quite a few semi-sweet wines of both colours, presumably for local markets), six of which they brought to the UK. Four were white. Chardonnay, Pinot Gris and Sauvignon Blanc were all well made, my favourite there being Pinot Gris 2017, which at £6.20 (to trade) I felt was way better than any similarly priced Pinot Grigio. Sixty days on lees gives it a brightness and texture, whilst it has that pear drop flavour with a touch of richness (13% abv) which seemed to combine a touch of Italy with a hint of Alsace or Baden.

My favourite white, indeed possibly my favourite wine, from Salcuta was Riesling & Traminer 2017. Made from 70% Riesling and 30% “Traminer”, it nevertheless tasted a bit like a nice Alsace blend. They kept it simple (stainless steel throughout). Production is a quite high 25,000 bottles, but it’s fresh and nice.

Their pink wine, Tamaiosa de Salcita Rosé 2017, won a Gold Medal at the Mondial du Rosé 2017 in Francelast year. It blends Pinot Noir (70%) with Muscat of Hamburg, and sees two months on lees, which I suspect is where this wine’s extra mouthfeel and character comes from.

The one red shown was a very interesting blend, Cabernet and Merlot (40% each) with 20% Saperavi, the well known Georgian red variety. After 18 months in new French oak it gets a year in bottle before release. I tasted Reserva 2015, which had a lovely rich nose with a palate that was spicy, rich and smooth.

TIMBRUS

The final estate is also based in Stefan Voda (the Purcari sub-zone, very famous in Moldova, where you will also find Château Purcari, now a massive wine brand in Central and Eastern Europe and a destination for coachloads of tourists). Timbrus is a little smaller that Salcuta (150 ha under vine). There is international input here, via Spanish co-owner Manuel Ortiz, who is also a renowned oenologist in Spain and south America. Ortiz professes to bring a European approach to all aspects of production, from vine planting to bottle. We certainly have an estate with ambition here, although prices (all under £10 to trade) are realistic.

Timbrus makes a single varietal Saperavi, and Saperavi 2015 (18 months in new oak) was dark and densely fruited. A bit oaky, but ridiculously cheap for the quality. Viorica 2017 is a 100% varietal from that grape variety, which I found tasted a little like Viognier, but with greater acidity and freshness. Rara Neagră 2016 comes from youngish vines, and is a pale and low alcohol (12%) red. Frankly I’m surprised this sees 12 months in new oak (apparently), as it spoils the balance for me of what otherwise I’d have expected to be a quite lovely wine. Fetească Neagră 2016 has 12.5% abv, and is pale as well. There’s a little more body, but also a fair bit of oak (same regime as above).

To summarise what I experienced here at this Tasting…well, I think you can guess.

- The wines really were quite astonishingly good for the money in many cases. There were several wines I’d buy, which you can probably guess from my descriptions. I think that the vast number of hectares under vine in Moldova mean there’s massive potential here, especially for really well made wines aimed at those wanting quality and value combined.

- Why the obsession with new oak? I suspect that when the pendulum swings for Western markets its movement is slow and takes a while to spot. I’m convinced that by dialling back the oak, wines of greater freshness and personality could be made. The formula of taking autochtonous grape varieties and covering them with new oak does rather hide their unique personalities, and new oak is not, in my view, the answer.

- It’s probably all too clear from my notes that I found the native varieties more interesting than the international ones. Every wine producing country on earth is trying to make Cabernet Sauvignon, Sauvignon Blanc, Merlot and so on. Moldova (as with neighbour Romania) has some wonderful local varieties that absolutely deserve to have a place on the shelf, and they also show a point of difference, not to mention regional typicity. I suppose the producers are fixed on the international market, but there’s a lot of competition out there. But remember, I’m writing here as a wine lover, not as a consultant on what the market wants.

- Where are the real artisans? Reading around the subject I notice that production is rather dominated by very big estates. Some articles virtually suggest that, as in Napa, many of these are geared up for coach parties rather than independently travelling wine lovers. After the fall of Communism it looks like land distribution saw much of Moldova’s agricultural acres, the large state-owned collective wine farms, falling into the hands of relatively few individuals, the opposite of what happened, to a large extent, in much of Central Europe. Georgia’s Qvevri tradition may in reality be just a tiny part of that country’s output, but it has attracted attention from wine experts and aficionados alike. This has led to a greater focus on the country, and we even have qvevri wines in a couple of UK supermarkets. Communism’s attendant effects here in Moldova mean that, unlike Czech Moravia, or Slovenia, there are no old guys making wine the old way, farming a few hectares in the hills, who can be wheeled out to excite wine writers. Everyone right now wants to be squeaky clean and modern.

So with Moldova we have a country with a vast vignoble, with genuinely massive potential. Whether they can live up to that potential depends on whether they can accurately judge what their target markets (certainly no longer Russia, but clearly the rest of Eastern and Central, as well as Western, Europe, the USA and beyond) want. Hopefully ultra-modern wines will give them an entrance to those markets, but I think that long-term success will depend on finessing what’s on offer. I think this can be achieved through offering regional typicity from local varieties. I do wish them well. They have come a lot further than I think most people realise.

Caroline Gilby MW’s book The Wines of Bulgaria, Romania and Moldova was published by Infinite Ideas in July 2018 as part of their Classic Wine Library.

Leave A Comment